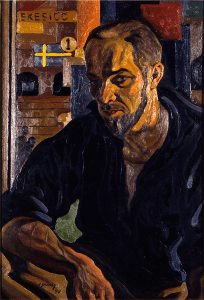

With his paints in one hand and a rifle in the other, Col. John D. Pusey lived life on the vanguard both literally and artistically. Smiling from behind a tidy mustache, his jacket heavy with military insignia, he hardly looked the part of an accomplished artist, but for Pusey art and war were simply two aspects of one grand adventure.

When asked to explain his seemingly incongruous successes as both an artist and an army officer, Pusey remarked, “Most painters are adventurers, and war provides the greatest excitement possible for the adventurous spirit these days.”

In his fearless pursuit of adventure, Pusey’s travels would bring him into contact with many of the great figures and defining moments of the 20th century and these encounters would come to shape a style of art as bold and unique as the artist himself, but just as John D. Pusey seemed poised to take the art world by storm he shipped off to storm the beaches of Normandy. Here is the story of his adventures in art and war.

John was born in Council Bluffs, Iowa where Pusey was a household name. Since pioneer times, the Pusey’s were bankers, senators, and entrepreneurs who, in the words of an 1891 biographical history of the county, were “universally admired and respected for their sterling worth.” The Pusey’s were an ambitious and industrious lot. In his yearbook, John Pusey’s younger brother Nathan declared that he would be president of the United States in 1968 – in 1953 he decided to settle for President of Harvard.

But as the class president and the class clown, John was admired and respected less for his sterling worth than for his sportive wit. According to his yearbook, John was always “wise enough to play the fool.” He drew humorous cartoons to amuse his classmates, stole pies from the cafeteria, played the comedic role in the school play, and teased the Latin teacher to the point where his peers jokingly recommended that he be chloroformed. The Pusey brothers were incredibly bright, but according to classmates, were always “concentrating on adventure.” John masterminded the pranks, but it wasn’t difficult to get his younger brother to play along.

John Pusey may have been known as a joker, but when it came to matters of art he was a serious and dedicated student. And after graduating high school in 1923, he attended three U.S. art colleges in three years, receiving a degree from the Yale School of Fine Art in 1926. But for an artist in the 1920’s, real adventure was not to be found in the halls of academia, but in the streets of Paris. And immediately after graduating John left for France to study at the Musee du Louvre and the Musee du Luxembourg – and to marry his first wife, studying at the College de Sorbonne.

The Pusey family money had all but dried up after the death of John’s father, and his mother had raised the three children on the $65 per week that she earned as a school principal. So with limited money and resources at his disposal, John lived the lifestyle of the Parisian bohemian, selling paintings to American tourists and working as a freelance magazine editor. And after exhibiting and selling work at several national shows, Pusey held a successful one-man show in Barbizon in the summer of 1928.

With money from the show burning a hole in his pocket, Pusey bought a bicycle and set out for new adventures. He rode his bike across Europe, traveling hundreds of miles from France to Madrid. It was in Spain that Pusey would discover his voice as a painter. Spending his days at the Museo del Prado, Pusey became obsessed with the bold and emotionally evocative works of Francisco Goya whose dark and subversive scenes of war and devastation would inform Pusey’s emotional pallet throughout his career. His color pallet, on the other hand, was not to be found anywhere in the museums of Spain, but rather in her bull pits.

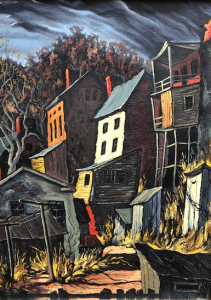

While in Spain he became fascinated with the “colorful spectacle presented at bullfights” – and this color and spectacle quickly became Pusey’s trademarks. Pusey widened his color pallet to a discordant extreme, employing increasingly intense colors. Perspectives were similarly exaggerated to disorient the viewer in ways that, in the words of one critic, were “exciting” and “unnatural.” And though his name would eventually become associated with narrative realism and the so-called “Regionalist” movement, it became apparent early on that, as far as Pusey was concerned, reality would always be subordinate to emotion. Pusey would, in fact, eventually drop reality all together, preferring to work with subjects from his dreams, memories, and – like Francisco Goya – nightmares.

In the early 1930’s, Pusey and his family traveled between France, New York, and Iowa, selling art where and when they could, but at the dawn of the Great Depression there were few opportunities of artists. As a free-lance artist seeing fewer and less profitable commissions, Pusey was grateful to receive work with the Public Works of Art Project – a short lived New Deal program which employed artists. Pusey set off for Iowa City where he joined a group of thirty-four regional artists who, under the direction of Iowa artist Grant Wood, were charged with creating a series of murals to be displayed in public buildings.

Faced with harsh the realities of the Great Depression, American artists in the 1930’s, inspired by the Mexican mural movement in the previous decade and imbued with new and urgent social consciousness, set their paintbrushes to work creating populist scenes in which common laborers were elevated, often heroic figures. And in 1934, as a leading figure a movement that became known as Regionalism, Grant Wood was on top of the art world. His paintings of idealized rural America, with their emphasis on community, simplistic living, and the dignity of labor appealed to a generation of dispossessed people trapped in the ever widening cycle of poverty.

But even as Pusey set to work painting scenes of tilling workers and rolling country sides for the PWPA, his private work told a story quite different than the agrarian utopianism of his mentor. In Pusey’s work, grain elevators were depicted in precise, sharply defined geometric forms, towering over desolate landscapes. Juxtaposed against rows of cattle, seemingly endless line of faceless workers file into an imposing building - the sky above them obscured by plumes of somber smoke. Even the thresher – one of Wood’s most celebrated figures – is seemingly consumed by fire-like stalks.

The popular staple of Social Realism – the ideal of the heroic laborer – was ever present in Pusey’s work, but was sometimes carefully subverted. Pusey’s laborers are never standing tall – they are uniform hulks hunched over assembly line machines, and if they derive any measure of satisfaction from their hard work it certainly isn’t evident on their faces. Pusey’s hero is a Sisyphean figure, bravely enduring endless and unavailing labor. All of the formal and thematic elements of Midwestern Depression Era art were present in Pusey’s work but they were stripped of all sentimentality.

He was at the epicenter of what would become a major art movement, but before that movement had a name Pusey was busy turning its conventions upside down. He simultaneously a part of and critic of the Midwestern scene painting movement, and this dual role was most perplexing. “His easel paintings of that era,” one critic writes, dealt with themes of labor and industry with “a dark realism” that was “quite foreign” to the prevailing tenants of the movement. And as people came to expect a standardized narrative of nostalgia and optimism from Wood and his followers, Pusey’s work was viewed with confused indifference.

With the WPA, the Government had successfully co-opted a populist art movement and Pusey had successfully masked social satire in its formal conventions. In his illustrations of the Great Depression, Pusey often included the very social, political, industrial, and financial institutions which were its cause. Within Pusey’s somber, seeming earnest works there is darkly veiled humor in which the mischievousness tendencies of the artist’s youth make a reappearance.

In a 1934 piece entitled “Cornerstone,” a group of fat, smiling suites - bankers and politicians - pat each other on the back. The men are applauded by an adoring crowd of photographers while a choir and a Girl Scout troupe sing their praises. Meanwhile, dominating the foreground, but unnoticed by the crowd of onlookers, two muscular men strain to lift a heavy cornerstone into place. By relegating the focal figures to the background, they are placed in a position of inferiority to the workers. And while ostensibly applauding the figures that provided the opportunity for these men to work, those same figures are implicated in brining about the wealth inequality and labor practices which made their desperate situation possible in the first place. Even in a scene of triumph and accomplishment there is an ironic sense of futility.

One can’t help but wonder if Pusey, now himself an anonymous worker involved in the systemized production of art, was representing himself in those workers. But if Pusey was resentful he expressed nothing but gratitude for the opportunity to provide for his growing family. As biographer R. Tripp Evans notes, Wood valued the sense of community engendered by the WPA, affectionately referring to his mural team as “my boys.” But Grant Wood’s “boys” were actually grown men and professional artists, some of whom came to resent the director’s confining and patronizing style of management. And while Wood walked away from the project disheartened and disillusioned, he and Pusey apparently parted on good terms, for it was Grant Wood who provided Pusey with the big break he had been waiting for.

In 1934, Grant Wood was at the height of his popularity as a regionalist artist when he was approached by Eli Lilly, the wealthy pharmaceutical manufacturer. Mr. Lilly’s use of scientific management had revolutionized the pharmaceutical industry, and in so doing earned himself a considerable fortune. Lilly’s seemingly endless energy, previously dedicated solely to pill manufacturing, broadened vastly as he applied his intensity to new interests of art, history, religion, and writing.

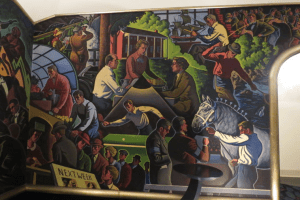

In a letter to Grant Wood written on behalf of Eli Lilly, it was explained that Mr. Lilly had recently purchased a new home, and he desired a mural painted on the third floor. The room was to be a library of sorts, a place for reading, inspiration and meditation. The mural was to be called “The House of the Interpreter,” and its themes were overwhelmingly grand: it was to have ten panels with headings like Courage, Research, Invention, and Growth, Religion; each panel was to be crammed with inspirational figures recent and ancient history.

Wood replied that he was too busy to take on such a large project, but recommended fellow artist John D. Pusey. In his response, Wood said, “I have every confidence in Pusey and can recommend him highly. He got his art training at Yale and has returned from seven years in France – an experience that leaves him with a fresh eye for American Material.”

Pusey would spend two years working on the massive mural, employing techniques he had learned from Grant Wood. But while the composition style was Woods, the painting style was Pusey’s own. Pusey convince Lilly to abandon the idea of painting historical figures, and to illustrate his 10 ideals in general scenes of anonymous labor. It was in painting this mural that Pusey’s mature style was established characterized by somber landscapes, dramatic lighting, and intense colors. During his time at the Lilly House, Pusey wrote to his friend and fellow artist Christian Petersen, relating how terrifying and exciting the project was. At times Pusey doubted the project would ever be finished, but in the end Lilly considered the mural a success. By the time Pusey left Indianapolis at the age of thirty one, he had become an integral part of the Lilly household.

In 1938, Pusey moved to California where he found employment in Hollywood as a set designer for Universal Studios and as a muralist with a firm contracted with the San Francisco World’s Fair. Known as the Golden Gate International Exposition, the fair would feature many art installations, and Pusey would paint eight murals and supervised the production of many others. Pusey left the fair just as legendary muralist Diego Rivera arrived. The organizers of the Exposition commissioned Rivera to paint a large fresco during the run of the fair as part of an interactive exhibit where people could watch artists create their work. Had Pusey stayed, he would have encountered two of the century’s greatest artist, Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo (the two were remarried that year in San Francisco).

When it became apparent to Pusey that “the United States was certain to become involved in the European War,” he enlisted in the National Guard and was commissioned as a 2nd Lieutenant in the 34th Infantry Division. Pusey was promoted to Captain and transferred to the Corps of Engineers where he designed camouflage patterns for the Army while he trained at specialized engineering schools, learning to defuse bombs.

When Captain Pusey arrived on the beaches of Normandy, he barely recognized the region he had painted years ago, back when he sold paintings to American tourists. He know the region well and had drawn a profile view map of the beach based on previous studies which he carried during the invasion. In a letter to his wife, Pusey described a nightmarish scene which he said, “looked like a giant junk yard – burning tanks, trucks, etc. and men or bits of men scattered everywhere.” For Pusey, the worst part of the invasion was watching others. “It was horrible to watch [them] going through what we had just done, but still they came in bravely without let up, boat after boat. I never saw one trace of cowardice shown by anybody and it makes you proud to be an American … When I looked at the Jerry defenses several days later I still don’t know how we ever took it, but take it we did and we are very confident and cocky now. I at least will never be afraid of anything anymore.”

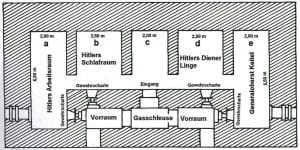

As a mine and booby trap expert, Major Pusey was often the sent into bunkers to clear explosives. “We were moving so fast then,” he related, “that the Germans had barely pulled out ahead of us.” With an accompanying sergeant, Pusey was assigned to clean out an elaborate underground bunker at Munster-Eiffel. “We were sent in to look for mines and traps…. names of high ranking German officers were still on doors to different rooms in the fortress.”

Known as Felsennest, this bunker was one of Hitler’s Fuhrer Headquarters – one of a number of official headquarters used by the Nazi leader and various officials throughout Europe during the Second World War. Adolph Hitler himself had stayed at Felsennest in 1939 and 1940 during the invasion of France. In the last chamber, a gas-proof state room labeled “Hitlers Arbeitsraum,” or “Hitler’s Workspace,” Pusey found something much more interesting than a bomb, he found paints.

According to Pusey, these paints “included rare German and Dutch colors, complete with pallets, paint knives and brushes.” Though he couldn’t prove it, Pusey liked to believe that the paints had once belonged to Adolph Hitler himself. “Only an aristocratic amateur such as Hitler could have owned such an outfit,” he observed. “It was far too elaborate for any professional to use.” Pusey was given permission to keep the paints, and shipped them to his residence in California and they arrived in fine condition. “I’ve enough paints there to last me for at least 10 years. I’m really going to enjoy civilian life now,” he mused.

When Pusey returned from the war, he put those rare German paints to good use. Of course it is impossible to know who actually owned the paints Pusey found in that German bunker, but Pusey relished the idea of painting a heroic war mural with paints “liberated” from a Fuhrer Headquarters.

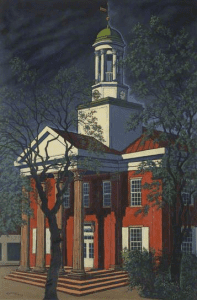

After retiring from the Army at the end of the war, Col. Pusey was called back into active duty as a result of the Berlin Airlift. He then served two years in Korea as a member of the engineer corps. Pusey finished out his military career by painting a large mural at the War College library in Carlisle, PA. The mural, which was completed in 1957, depicted every branch of the military in a variety of sciences from World War II. Pusey spent two years working on a canvass 50 feet long and eight feet high which featured over 200 figures.

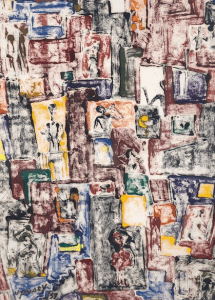

Pusey described his philosophy as a muralist when he said, “Any good mural design should have no perspective or atmosphere about it. It looks the same close up as it does from a distance. The mural is supposed to supplement the architecture, not detract from it. My idea is to make [panels] like a medieval tapestry in which the subjects do not have to be to scale. They are unrelated groups of figures in a montage that covers one general subject.”

The end of the Second World War would come to discredit the regionalist art movement with which Pusey was affiliated, and the styles of Regionalism and Social Realism would lose their status in the art world. In a period of relative peace and prosperity, the heroic ideals WPA art faded into the background as abstraction took center stage. The Cold War further marginalized the Regionalist style which, with its emphasis on farmers and workers, drew negative comparisons to communist propaganda.

As the relatively conservative and traditionalist style of the Regionalists fell out of favor, many American murals from the 1930’s and 40’s were removed or destroyed. During this period, murals by John Pusey were lost in Cedar Rapids and Council Bluffs, Iowa.

As an artist, Pusey was always more interested in emotion and color than he was with subject or proportion, and with the rise of abstract expression, Pusey happily abandoned the constraints and trappings of the WPA style and began experimenting with shape and color. Profiting by his experience in the army with color-blind tests and camouflage techniques, many of Pusey’s later works were often experiments in stereo-vision meant to create the illusion of three-dimensionality.

In 1957, John Pusey joined the faculty of the Dickinson College in Carlisle, Pennsylvania as the artist-in-residence. His course in the fundamentals of painting and design were among the most popular at the college.

John Drake Pusey once said he had sold over 500 paintings in his lifetime, but if he was to be remembered he would be remembered as a muralist. When he considered his legacy as an artist mostly affiliated with the depression-era style, he didn’t seem too concerned. In an interview with a local paper, he once said, “if art was good in its time, it is good forever.” John Drake Pusey died in 1966.

Special Thank you to Dave Willmarth and family for providing images of artwork.

Click HERE for more information on Council Bluffs History.