Before Council Bluffs had street lights, it had giant towers that mimicked the moon.

For most people living in Western Iowa, the first time they encountered electric light was at the circus. In the 1870’s and 80’s, the Daily Nonpareil newspaper was filled with stories about Thomas Edison and the wonder of electric light, but outside of New York and Paris, few had encountered the technology, and could only dimly conceive of its brilliance.

Traveling Circuses not only showcased animals and performers, but also wondrous new technologies. When the “Great Inter-Ocean” circus came to Council Bluffs in the summer of 1880, an advertisement in the Daily Nonpareil promised to showcase many wonders, but the electric light got top billing. Viewers were told the entire circus would be, “brilliantly illuminated day and night, above the brightness of the sun, with a $50,000 electric light, the finest in the world, generating an intense but soft and dazzling light, equal in power to 165,000 candles.”

The circus itself was a disaster, and the newspaper issued an apology to the hundreds who attended, calling the show, “a fraud and an imposition,” but conceded that the light was fine sight, well worth seeing. While those in attendance quickly forgot the clowns, the electric light stayed burned in their imaginations. The old Dohany Theater presented a comic play titled “Electric Light.” The paper was filled with stories of brilliant lighting displays in far-away cities, and some close to home. In 1881, the paper reported that the City Council of Keokuk Iowa ordered their gas street lamps turned off as a single electric light from a passing river-boat steamer was sufficient to light the whole town. A year later, Tipton, Iowa, a town of only 1,500 inhabitants, was lighted by electric light.

Once people had experienced electric light, gas seemed dim and dirty in comparison. Almost daily, the paper published editorials form citizens urging the adoption of this new technology. One reader wrote, “The electric light is something that Council Bluffs should be busily engaged in taking up … all the principle cities of the west will be utilizing the electric light, and Council Bluffs should not be behind the boom.”

Darkness was metaphorically associated with ignorance, and electric light came to symbolize its opposite – enlightenment, progress, and prestige. It was fashionable for prominent members of the community to travel west and relate their experiences to newspaper readers back home. In these accounts, the author expressed wonder at western towns such as Salt Lake City which was, “lighted by the electric light, and is a grand success,” and expressed hope that, “the day is not far distant when Council Bluffs will be similarly supplied.”

But as travelers tried to describe the brilliance of electric light, they often struggled to find words. Comparisons to thousands or hundreds of thousands of candles were a helpful metric, but it was difficult to imagine that many candles.

While candle light was warm and flickering, electric light was cold, constant, and alien. The metaphor most often employed it describe it was the moon. Standing under an electric light at nighttime was like standing outside on a night lit by a bright and brilliant full-moon. One report to the local paper invited people to imaging standing outside under a brilliant moon and reading a pocket watch as easily as if was high noon.

An 1882 editorial in the Daily Nonpareil demanded, “Council Bluffs has been in darkness long enough. We need the electric light and we will have it.” This and similar articles greatly overestimated the reliability of existing systems while greatly underestimating their cost. “Estimates made prove that this city could be thoroughly lighted by that means for at least one-third of the cost of the miserable light now furnished.” When reporting on the late-night shenanigans at the city’s more notorious establishments, writers would often suggest that such dark deeds would cease under the illuminating presence of electricity; Each new lightbulb, they asserted, was as good as one new policeman.

Under increasing public pressure, the Council Bluffs City Council Committee on Streets and Gas Lights took up the issue in October of 1882. Word had spread that the neighboring city of Omaha had formed an electric light company, and the local Board of Trade swiftly passed a resolution that they would assist with the formation of a light company. The committee sought to contract with the Brush Electric Light Company which had installed a successful arc light system in Cleveland years earlier. The City Council passed a resolution and, in October of 1883, two rival companies were granted permission to install lights in the city.

Large dynamo generators were installed and, just two days before Christmas, a light was turned on over the new city jail (to “illuminate the surroundings sufficiently to enable officers to see prisoners that may attempt to escape.”). The newspaper reported, “The electric light was a decided success last night and shined forth in all its brilliancy from early evening until late. The brilliant light was the admiration of all.” The success was short lived, as one company issued a notice on Christmas from their offices at the Odd Fellow’s Building requesting citizens, “not to interfere in any way with the lamps, wires, etc.” The wires, which were poorly insulated and strung over long distances, were proving to be dangerous.

The first customers to the new lighting companies were businesses on Broadway, one of which boasted that electric light made their store “more attractive, convenient and satisfactory to our customers and ourselves.” Rival stores took notice as their competition extended their hours into the night. Another early customer was the Dohany Theater who turned on their light for the first time during a graduation ceremony for Council Bluffs High School students in 1886 where it was said that the light reflected the bright minds and moral character of the graduates. In October of that year, people crowded around to see a lighted window display at People’s Store, and the new County Court house was lit from “tower to basement” with four giant bulbs in the top tour, illuminating the street below.

A prominent Citizen of Council Bluffs named Thomas Officer traveled the country examining lighting systems in other cities. He returned to Council Bluffs to form the Council Bluffs Lighting Company. Officer wasn’t interested in lighting individual businesses – he wanted to light the whole city. As moonlight was the prevailing metaphor, Officer sought to create artificial moons. Spaced at intervals around the city, he proposed the city erect massive towers resembling oil derricks, each capped with four large arc lamps. While businesses had banded together to pay to light a few streets, Officer wanted to light all of the streets at the expense, not of the local business community, but of the city.

The electric light companies rightly surmised that as people became used to the light, they would come to rely on it and demand more, even at greater expense. Many began to see light not as a novelty, but as a necessity, and people began writing to the newspaper asking the city for light in various places. “Everyone appreciates our clear moonlight nights,” one person wrote, “for nature’s great lantern hangs above us and penetrates every nook and corner. The only substitute man has invented that approaches moonlight, is the mast or tower system of electric light. Why should we sit in darkness … and see our smaller sister cities brilliantly illuminated?”

In 1887, the city passed an ordinance calling for the Council Bluffs Electric Light company to regulate and inspect light instillations. To illustrate the effect of his proposed, city-wide system, Thomas Officer invited the City Council and local reporters to view the lights from the new county court house from numerous points of observation. The council was astonished at the power of the lights, even as it cast stark shadows in certain areas. Officer suggested to the Council that the problem of street lighting had been solved and the answer was to install massive light towers at seven points about the city, eliminating the need for street lamps.

On September 1st of 1887, a special session of the City Council unanimously adopted a proposition and contracted for the creation seven electric light towers, each with four lights of 8,000 candle power. The lights were to be run from dark until daylight at $20 for each light per month. When the City Council decided on locations for the towers, property owners across the city objected and petitioned the Council for one of the towers to go up in their neighborhood. A newspaper editorial responded to this concern, stating, “everybody cannot have one in front of their doors, and hence will have to be content with the council’s dictation in the matter.”

The massive towers were 150 feet tall, powered by Thomson-Houston dynamos. Each contained an elevator to carry a person to the top to service the carbon filaments. In retrospect, it was foolish to place lights so high, only to light rooftops and the night sky, but it seemed sensible at the time. Towers were erected on the Southwest corner of Oakland Avenue and Ross Street; in front of the Methodist church on Broadway; on the corner of Frank and Pierce streets; by the fountain on Broadway and Fourth Street; Sixth street and Twelfth avenue Broadway and Eight street; and at the new county court house.

Early ARC lights were super bright and capable of lighting a large length of street, but they would sometimes flicker, creating a disconcerting strobe effect. The lights were, as proponents asserted, more cost effective than gas or oil lamps. However, the carbon rods needed to be replaced after a short period, and this became a full time job for the city. Also, the lamps produced excessive heat and often burned or electrocuted technicians.

Despite these shortcomings, the towers were well loved. But they were beset with problems from the very beginning. The lights were expensive to maintain, the towers were precariously tall, and the electrical wires strung across the city were dangerously exposed. It became apparent early on that the cost of the tower system was a fiction. In January of 1895, a bill presented by the electric light company staggered the City Council. City Buildings went dark as all arc lights and incandescent lights were turned off in response to the expense. Despite these austerity measures, the City claimed that the electric meter still persisted in its “extravagant prevarication.” The city accused the company of over-charging, and quickly moved to regulate meters and meter attendants.

The City Council battled with the Council Bluffs Gas & Electric Light Company for years. The Council complained that the cities light towers were broken more often than they were operational. The company disputed these claims. In frustration, the City hired a city electrician and supplied him with the necessary instruments for testing the lights twice a week on each circuit, and instructed him to make a weekly report of voltage and deficient lights.

When the electrician reported systemic problems, the light company pushed back, prompting the city to bring in an outside expert – an electrical engineer from Omaha. After concluding his investigation, the engineer told the City Council they had been duped into paying for a service they were not receiving. Of the lights tested, not on came up to standard. The city refused to pay the company.

Less than ten years old, the once miraculous light towers were now an embarrassment. Thomas Edison had invented a superior incandescent bulb with a filament material that could withstand high temperatures. Edisons’ bulbs were considerably more reliable than the hated arc towers which shined down on Council Bluffs like the Eye of Sauron. As fixtures were standardized and power distributed, electric lights came down to earth, and the towers came to be viewed not as technologically marvels, but as ugly and dangerous relics.

Many citizens wrote to the paper to complain about the rusted, leaning, often inoperable towers. During a storm, one of the towers came crashing to the earth. Thieves stole thousands of feet of cooper wire strung to a tower at Lake Manawa. A service man was killed when he came into contact with wires supplying power to one of the towers.

Despite the accidents and public concern, the electric company refused to repair the towers, claiming they belonged to the City. There was nothing in the records, they argued, which made them liable for the needed repairs. Unable to get the company to take action, the mayor declared the towers a public nuisance and ordered their bases to be coated in cement to prevent them from falling over as the city explored options to have them removed.

When the Council Bluffs Gas and Electric Light Company declared bankruptcy in 1899, the City put out an advertisements for new contractors but received no bids. City officials debated the benefits and drawbacks of municipal ownership, but eventually decided to do a second, larger campaign to attract contractors.

The towers stood neglected and barely operable for years. The city Alderman declared that he “shuddered at the sight of the lofty light pinnacles” which were rickety and unsafe. At a meeting of the City Council in 1908, the Alderman pressed officials as to who will be responsible if one of the towers fell and killed somebody. “The towers are a constant menace,” Alderman Morgan said, “If property owners object to having them taken down, I will suggest that they be required to sign waivers, exempting the city from damage in case the towers fall and smash things.” A representative from the new power company stood up and accused the city of negligence.

When the towers were taken down, it was reported that the steel tubing of which they were constructed was so rusted that it was less than a sixteenth of an inch in thickness in places. When the workmen cut into the towers, they found that they were shells of rust, and they could break off pieces by hand.

Like the rest of the county, Council Bluffs would come to take electric light for granted. But in the early 20th century, people stood on street corners and stared up to marvel at the brilliant globes which shown from the heavens. These artificial moons were obsoleted and forgotten, except to those who saw them when they first went up. Those people would never forget the first time they witnessed the dawn of the modern era and sensed the world would never be the same.

Click HERE for more information on Council Bluffs History.

Photographs:

1. A moontower in San Jose, California, 1881.

2. The County Court House in Council Bluffs which had 4 arc lights in the tower.

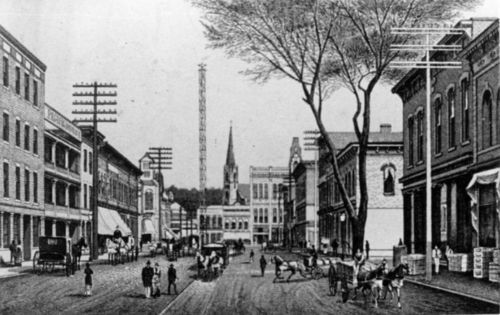

3. A view of Broadway, looking east, circa 1890. A light tower can been seen in front of the church.