Around 4:30 p.m. on Monday, September 26, 1881, “a terrific explosion of giant powder at the Chicago & Rock Island depot,” shook the city of Council Bluffs, as reported in the September 28, 1881 issue of the Avoca Herald. The reference to ‘giant powder’ is essentially dynamite. Giant Powder Company in California produced it and the name became synonymous with the high explosive, according to Evelyn Rose who wrote an article about Giant Powder Company. A freight car loaded with the ‘giant powder’ was sitting in the Chicago, Rock Island and Pacific (CRI&P) rail yards when “a spark from the engine ignit[ed] the roof of the car containing the powder.” Rail yard employees tried to extinguish the flames but were unsuccessful. General Agent Stevens of the CRI&P Railroad was notified and dispatched two engines to try and move the car full of explosives. However, the Daily Nonpareil, on September 27, 1881, described that “when the engines reached the spot, the fire was regarded to have made too much headway to attempt to interfere with the car.” Stevens communicated this development to the CRI&P railroad employees and most were able to flee or find cover to escape serious injury. The resulting explosion created “a hole in the ground at least fifteen feet deep and forty-five feet in diameter,” according to the Daily Nonpareil.

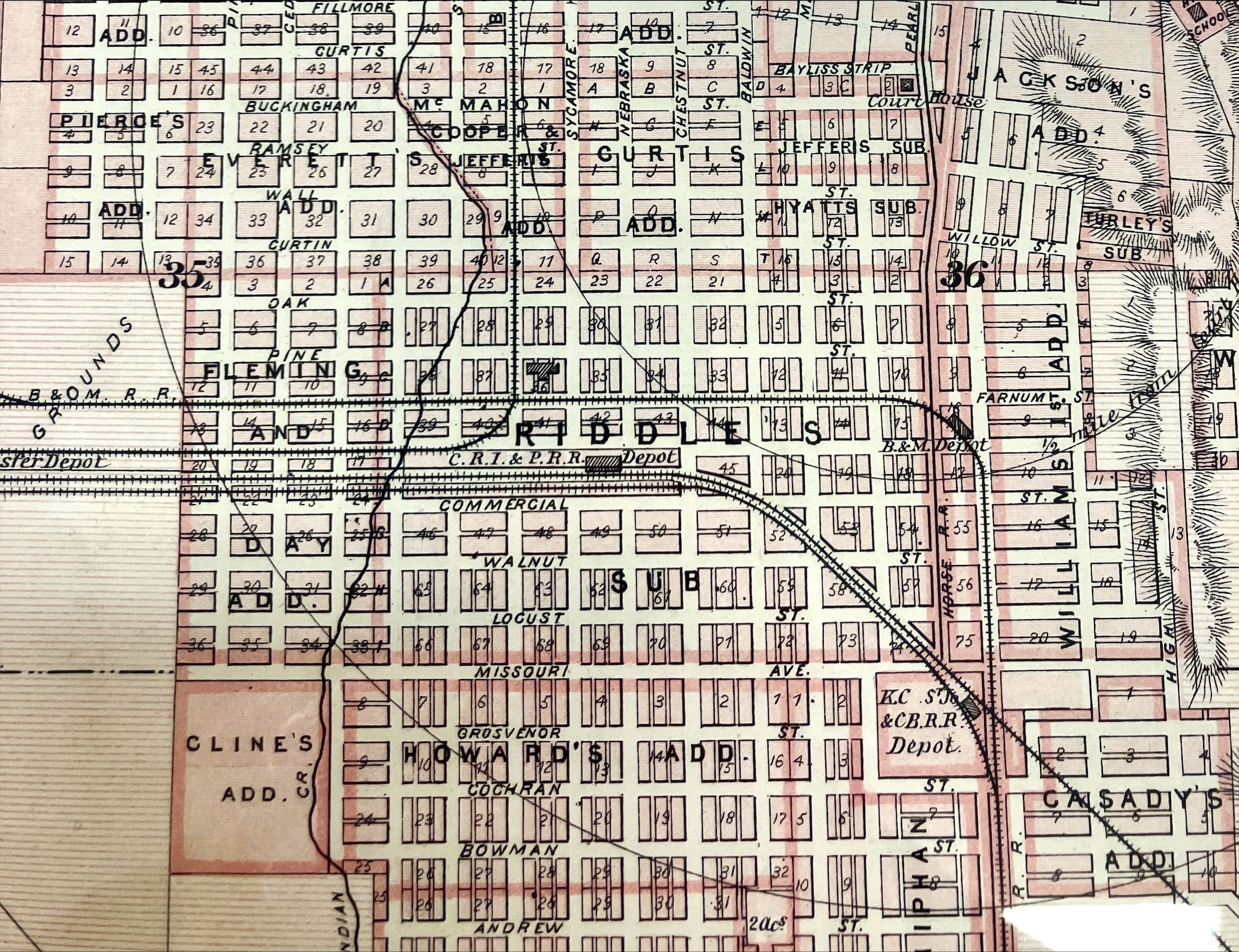

A couple days prior to the explosion, the railroad car full of “common blasting powder” reached Council Bluffs on the CRI&P line. The CRI&P yards were located between 12th and 13th Avenues and spanned from 9th to 15th Street. The freight depot was located on the southwest corner of 11th Street and 12th Avenue, with the roundhouse located nearby. The car full of powder was supposed to go on to Colorado but Union Pacific Railroad “refused to receive the dangerous freight and the car was sent back to the Rock Island yards,” and parked near the roundhouse.

Coincidentally, the same day of the explosion was the memorial service for President James A. Garfield, who died on September 19, 1881 from medical complications after an assassination attempt. “Nearly ten thousand people were in and around [Bayliss] park when the most deafening sound shock[ed] the buildings and staggered persons a mile away from the scene of the wreck.” A dense cloud of smoke rose from the south end of town and people originally thought a gas tank had exploded. The fire department didn’t wait for an alarm. They heard the explosion too and started heading in the direction of the smoke from the CRI&P rail yards.

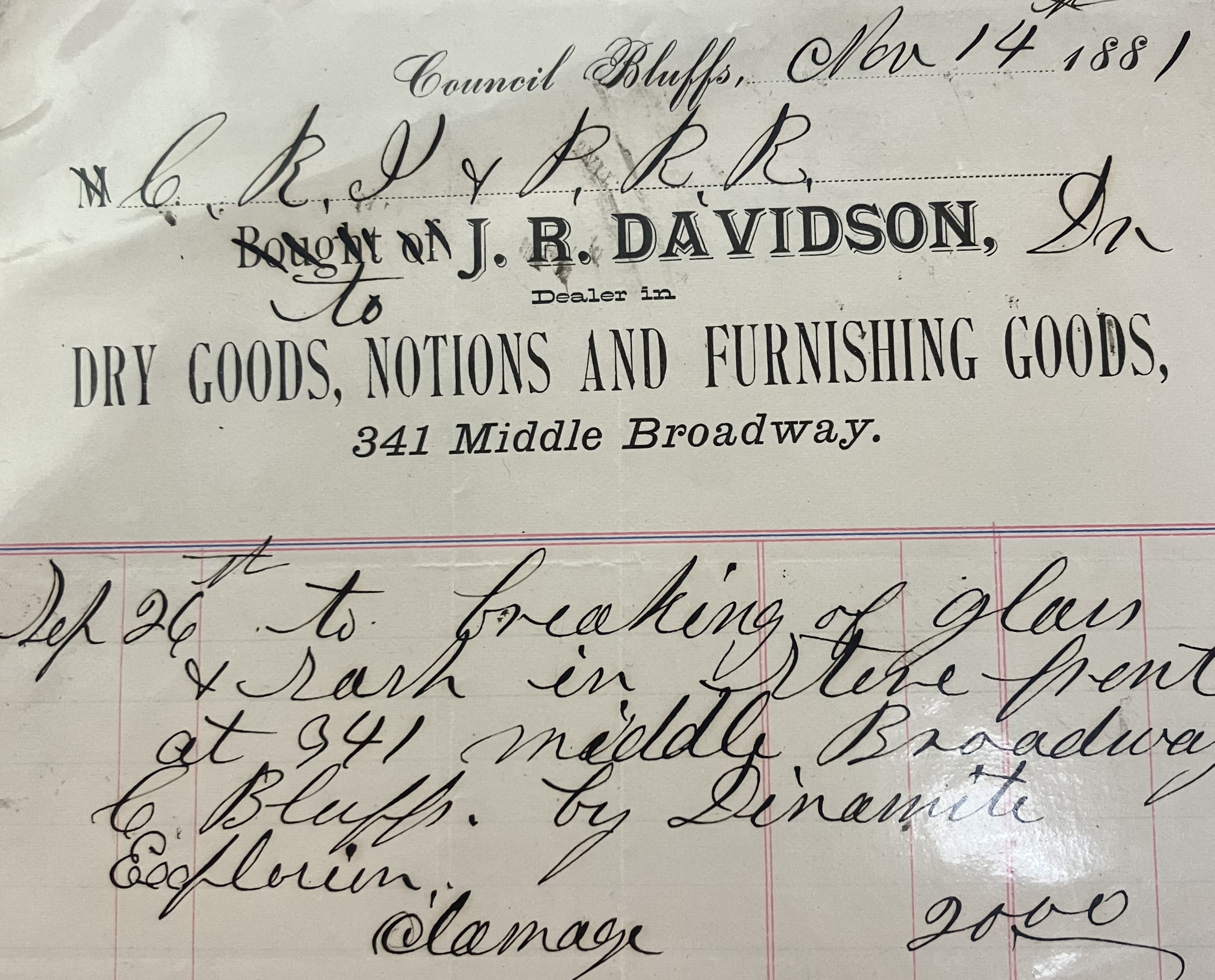

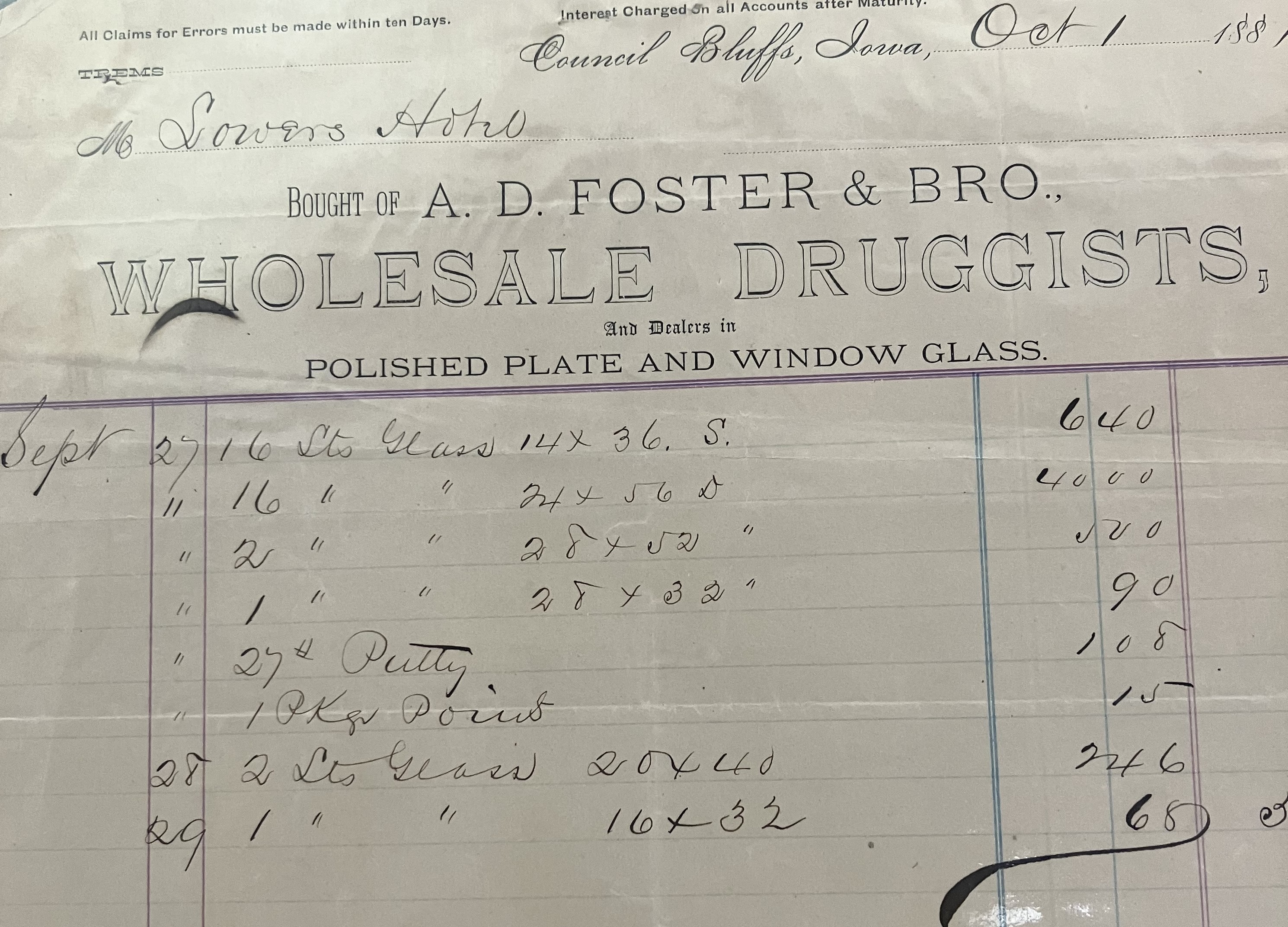

On arriving at the scene of the explosion, the Avoca Herald reported nearby “houses were found fairly dismantled, windows shivered, plastering torn from the walls, chimneys thrown down and brick carried a distance of nearly half a mile away from the disaster.” The CRI&P roundhouse was demolished as it was the building closest to the explosion. There were three engines inside of it. “They were half covered with the ruins of the roundhouse and badly injured otherwise. One had the strong steel plate around the boiler ripped off and the bolts are twisted into inextricable confusion.” In addition to the roundhouse being destroyed, “repair-shops of brick and a frame freight house [and] forty or fifty freight cars” were completely ruined. Several passenger coaches more than 300 feet away were damaged as well. Outside of the CRI&P rail yards, “large windows in all parts of the city were shattered [and] the plastering tore from houses.” The blast reportedly affected areas outside of Council Bluffs. “Large windows were even broken in Omaha, on the opposite side of the Missouri, and as far as Missouri Valley, twenty miles north of us.” The Avoca Herald estimated the damages would “reach into the hundreds of thousands of dollars.”

Some serious injuries were reported of people near the blast, mostly from flying debris but no fatalities were recorded. The Avoca Herald reported that luckily, nearly everyone was attending the memorial service for President Garfield, otherwise there would have been a great number of fatalities associated with the explosion. In addition, if it had happened 30 minutes later, three express trains would have been passing by the CRI&P rail yards at the time the explosion occurred.

Sources:

Avoca Herald article from September 28, 1881

Daily Nonpareil articles

Rose, Evelyn. "Giant Powder Company: Historical Essay." FoundSF, https://www.foundsf.org/index.php?title=Giant_Powder_Company